Empirics around Heckscher-Ohlin

Introduction

The Heckscher-Ohlin offers some bold predictions but, at the same time, relies on some heavy assumptions. Some interestig predictions that may be brought to the data are:

- Countries with higher capital endowments should specialize in capital-intensive industries and export capital-intensive goods

- Wages and rental prices should converge across countries

On perhaps unrealistic assumptions we can list:

- Perfect factor mobility between industries Can we really re-allocate a desertic land area to the production of timber?

- One sector is always capital intensive, and the other labour intensive Formally, this means that capital intensities do not switch at any given price level. This restricts the possible set of production functions

- Identical production technologies exist in both countries

- Identical preferences exist in both countries

The Leontief paradox

One of the most well-known tests on the Heckscher-Ohlin model was performed by Wassily Leontief in 1953. His analysis aimed to test the model’s prediction that countries should export goods that intensively use the country’s abundant factors of production. In the case of the United States, a country with a high capital endowment relative to labor, the Heckscher-Ohlin theory predicted that the U.S. would predominantly export capital-intensive goods and import labor-intensive goods.

Leontief used input-output tables to analyze the factor content of U.S. exports and imports. Surprisingly, his findings contradicted the predictions of the Heckscher-Ohlin model. He discovered that U.S. exports were less capital-intensive and more labor-intensive than its imports. This unexpected result became known as the “Leontief Paradox.” It challenged the validity of the Heckscher-Ohlin model and sparked significant debate in the field of international economics.

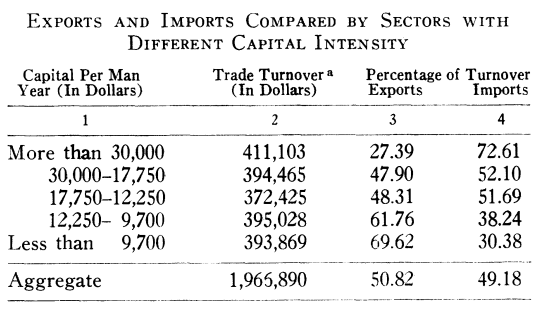

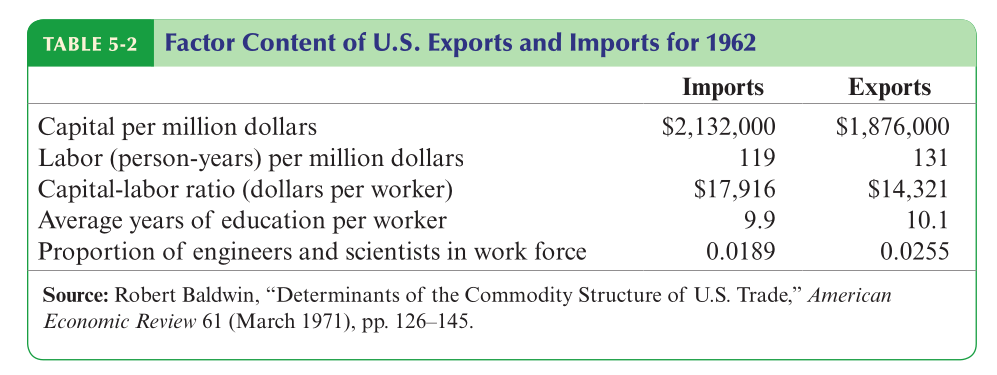

Other tests have nuanced the positions. Robert Baldwin re-examined the data for 1961 and revealed again that capital-intensive goods are more likely to be imported than exported. However, exports used more educated labor than imports, and also employed more engineers. In that sense, export were more skill-intensive, and the US is abundant in skilled labor.

Another study (Bowen, Leamer, Sveikauskas) focused on 27 countries and considered 12 production factors. They compared the factor intensities of exports and imports to factor intensities of the countries, and classified those that followed the pattern predicted by the model. For instance, a country that exports a capital-intensive good when the country is capital-intense confirms the Hecksher-Ohlin predictions. However, the success was only 61%. These results confirmed that the Leontief paradox was not an isolated case.

These set of tests really casted doubt on one of the main hypothesis of the model: production functions are identical across countries.

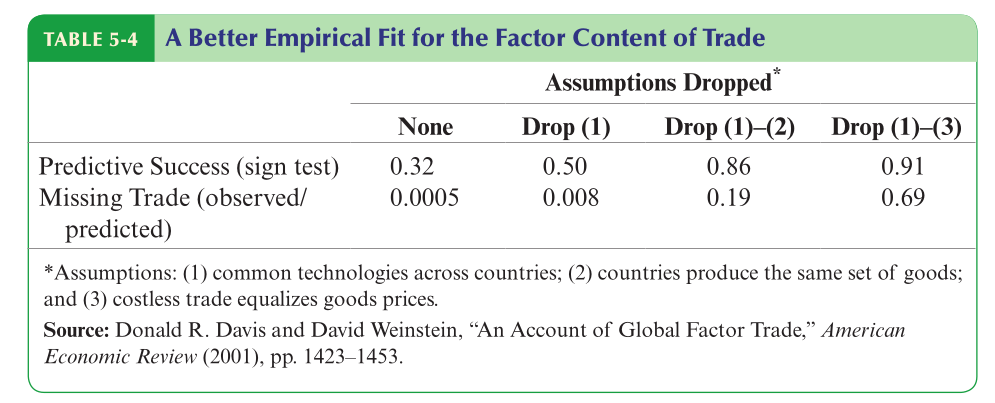

Removing restrictive assumptions increases the performance of the model, as shown by Davis and Weinstein:

Winners and losers

The Hecksher-Ohlin model (in fact, the Stolper-Samuelson theorem) predicts that countries that specialize in capital-intensive industries will experience a rise in the relative price of capital, and a fall in the relative price of labor. The prediction also holds for other factors, in particular, high-skilled and low-skilled workers. In economics, we call high-skilled workers those who have accumulated multiple years of education, typically obtaining a college degree.

According to the Stolper-Samuelson theorem, a country that has a relative abundance of high-skilled workers (like the USA) should export high-skilled labor-intensive and, thus, the the wage of high-skilled workers should rise. This means that high-skilled workers in the USA should benefit from trade and globalization. Moreover, because low-skilled workers see their wages decrease, they should oppose to trade and ask the government to put in place tariffs and other protectionist measures.

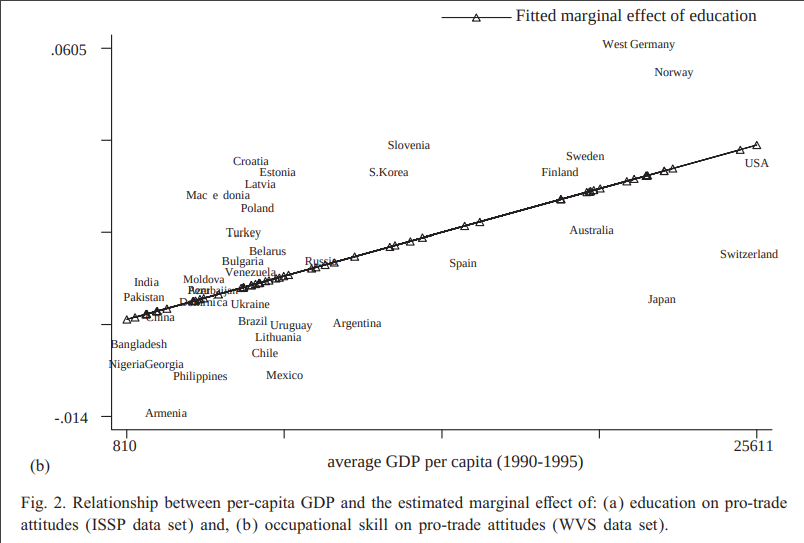

The data shows that this seems to be the case.

In this graph, the average GDP per capita approximates the relative abundance of high-skilled workers: countries with high GDP per capita have more high-skilled workers. For each country, the authors study the relationship between the education of an individual and whether he is pro-trade. For instance, a highly-skilled person in Bangladesh should not be pro-trade, because Bangladesh has abundance of low-skilled workers. In contrast, a Norwegian with a college degree should be pro-trade, because Norway has abundance of high-skilled workers. The plot confirms the prediction of the model.